Delay sought; staffing critical

New laws require health care facilities to implement minimum employee ratios

By Bethany Bump

This article appeared on the front page of the print edition on Tuesday, November 9, 2021

Will Waldron / Times Union

In the face of staffing shortages, a large hospital association is asking New York to delay new laws that will require hospitals and nursing homes around the state to establish and maintain minimum staffing levels.

Albany

A regional association representing 50 upstate New York hospitals is calling on the state Department of Health to delay implementation of new laws that will require hospitals and nursing homes around the state to establish and maintain minimum staffing levels.

The Iroquois Healthcare Alliance — which represents hospital systems in 32 upstate counties, including the Capital Region — argues implementation of the laws by Jan. 1 is infeasible given current widespread staffing shortages plaguing health care facilities statewide.

In a letter to then-state Health Commissioner Howard Zucker last month, IHA President and CEO Gary Fitzgerald said the organization’s primary opposition to the law relates to its timing, as hospitals are currently experiencing unprecedented workforce shortages that he says have been exacerbated by the state’s coronavirus vaccine mandate for health care workers and a recent court decision striking down religious exemptions to the mandate.

“The current workforce crisis facing hospitals across upstate New York is dire,” Fitzgerald wrote in the letter.

Hospitals and health systems stretching from Albany to Buffalo had over 2,000 open registered nursing positions prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, he said. After the pandemic hit, some 6,000 workers were furloughed as elective surgeries were canceled to make room for a potential wave of patients, which modeling projections at the time indicated would overwhelm hospitals.

“Today, vacancy rates remain extremely high, and our members are functioning in crisis mode, unable to accept transfers, canceling elective procedures, reducing operating room capacities and a general slowing down of daily patient care, all related to and a direct result of workforce shortages,” he wrote.

One of the new laws, which was passed this spring by the Legislature and signed by former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo, requires hospitals to form clinical staffing committees made up of at least 50 percent nurses and direct-care staff. Committees would be charged with developing annual staffing plans that include specific guidelines or ratios for determining how many patients a nurse can be assigned at one time and how many nurses and ancillary staff should be present on each unit and shift.

Staffing plans would be due to the state Health Department by July 1 each year, and the department would then be charged with investigating violations of the plan and could demand corrective actions or impose civil penalties.

Another law requires the state health commissioner to set minimum staffing standards at nursing homes that include at least 3.5 hours of nursing care per resident per day. At least 2.2 of those hours must be provided by certified nurse aides and 1.1 hours by licensed practical nurses or registered nurses.

Facilities have until Jan. 1 to comply and may face penalties if they fall short.

In his letter to Zucker, Fitzgerald asked that any regulations resulting from the laws contain “safety valve” language clarifying that the department would not penalize facilities where there are significant and longstanding workforce shortages. The laws currently include language allowing the commissioner to factor in emergency situations and acute regional labor shortages when deciding whether to penalize facilities, but Fitzgerald told the Times Union he believes that language is too vague.

“We’re hoping that the commissioner’s office and the DOH people who are putting the (regulations) together… can be more clear as to what kind of flexibility there will be,” he said.

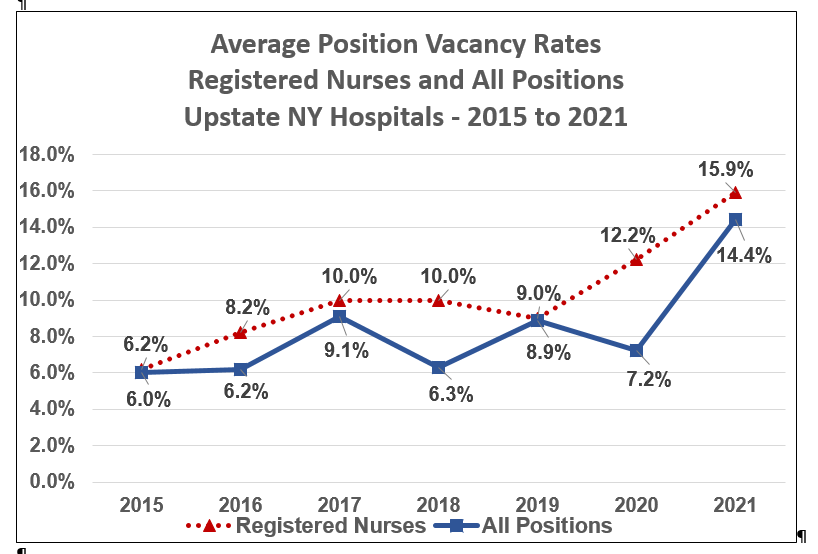

Vacancy rates for registered nurses had been on the rise for several years prior to the pandemic, IHA figures show. In 2015, they were about 6 percent at upstate New York hospitals, and rose to between 8 and 10 percent over the next four years. They are now at 16 percent. Vacancy rates for all positions, meanwhile, have doubled in the last year from approximately 7 percent in 2020 to over 14 percent currently, IHA figures show.

Fitzgerald said he expects vacancy rates will get worse should courts ultimately decide religious exemptions to the state’s vaccine mandate are not allowed. Some 1,300 employees at 33 upstate hospitals surveyed by IHA have requested religious exemptions, he said.

“This is like the worst time that you could implement two new laws which impact staffing when we’re desperately trying to maintain staffing levels,” he said.

Fitzgerald said he has not received confirmation or response from the department regarding his letter, but his organization has also been meeting with state Senate and Assembly staff about possible tweaks to the effective date of the laws — the timing of which would require the Legislature to return for a special session.

“We’re just asking,” he said. “We’re trying to make sure they understand how desperate hospitals are right now for staff.”

Jeffrey Hammond, a spokesman for the Department of Health, said his department had not received the letter from Fitzgerald but added that it’s prohibited from changing the effective date of the new laws anyway because they are statutorily mandated.

Regulations pertaining to the minimum staffing requirements for nursing homes and hospitals were filed with the Department of State and will be published in the State Register for public comment Nov. 17, he said.

The New York State Nurses Association, which advocated heavily for minimum staffing laws, said employers need to step up and work with unions and nursing schools to create a massive jobs program in response to the staffing issues that have plagued their facilities for years.

“If we don’t act on improving patient safety coming out of this experience, when will we ever learn?” said Pat Kane, executive director of the association. “Safe staffing cannot wait any longer. … Employers should understand by now that underpaying and under-staffing are dead-end strategies. Several hospitals went completely in the wrong direction, laying off employees after the pandemic and freezing hiring despite existing vacancies. Employers should create the conditions that allow workers and patients to thrive, and this law finally holds them accountable in a way that the public deserves.”